The well-known English rock and pop band, 10cc, had a major success with their 1976 album, How Dare You. One of the LP’s songs became a Top Ten single and was partly responsible for the band’s dizzying success.

The song contains the lyrics ‘Art for art’s sake, money for God’s sake’. The words refer ironically to the dilemma most artists face: do you produce works of beauty because they’re beautiful, and for no other reason? Or should they serve a range of purposes, not least allowing you as the work’s creator to survive?

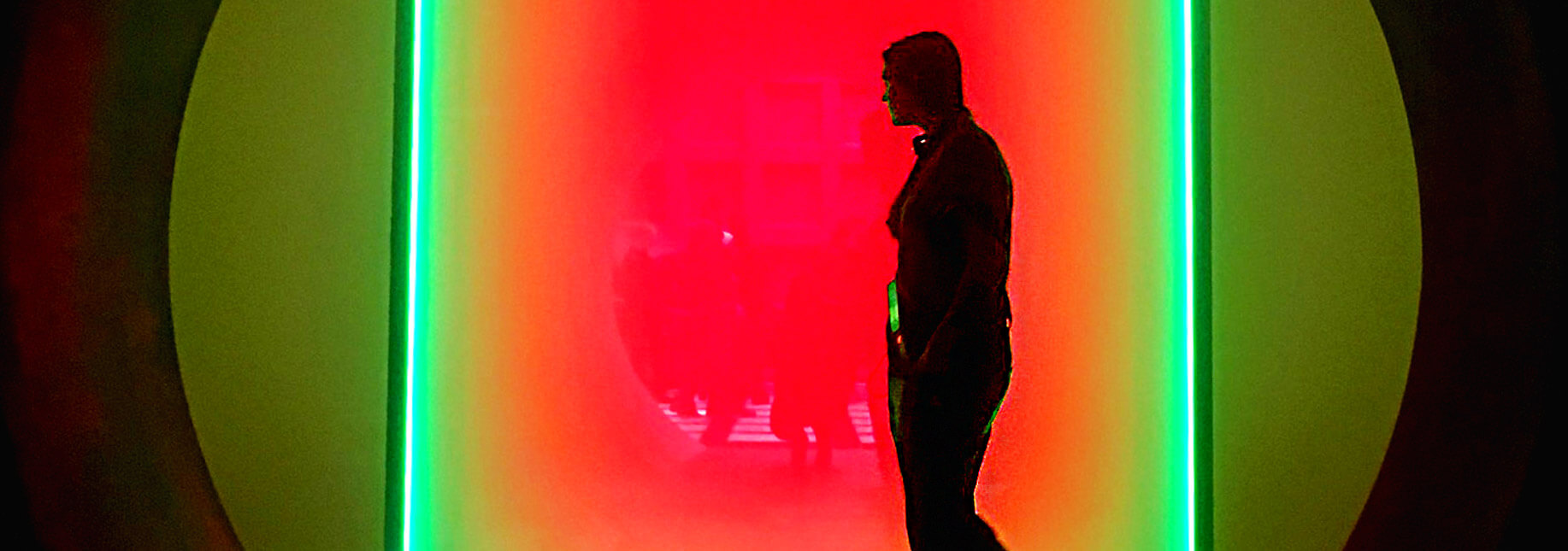

As a professional sculptor and curator of other artists’ work, I confront that dilemma every day of my creative life. I knew my decision to explore Tasmania’s Museum of Old and New Art (MONA) was bound to elicit some reactions. Why did I go? What were my impressions?

I went out of compulsive curiosity. Art for me is surrendering to improbability; either looking at an idea presented in a completely different way to anything ever expressed before, or creating a new idea myself.

As an artist, I don’t believe in art for art’s sake. I’m with the British philosopher and writer, Alain de Botton, who opposes the idea of art living in a hermetic bubble and doing nothing for our sometimes difficult world.

Two world views on art

It’s the first of two world views on art he criticised in a 2012 TED talk. The second belief he takes a shot at is the notion that art and artists shouldn’t have to explain themselves for fear of spoiling the magic.

He pulls the rug from under the feet of people who may have no idea what the art in a museum or gallery means but are too ‘serious’ to admit their ignorance.

I steer clear of political and religious discussions. For a start, I’m not well enough informed on either to express a worthy opinion. And even if I were, I prefer to avoid the conversations on the grounds that we have enough division in the world without adding to the clamour.

Instead, I take the approach that successful art represents the eternal battle between good and evil; between what uplifts us mentally and spiritually, and what lessens or defiles us. Art gives us ways of seeing and remembering graspable truth with most human distractions stripped away.

Those who aspire to lead us, much as some might protest, always try to dictate what we consume, including art and its very public expression, sculpture. MONA supporters, like most avant-gardists and revolutionaries, are no different.

Examples of misguided, violent, and destructive approaches to art appreciation abound in history. For this discussion, let’s briefly look at a recent example of cultural corrections (which could also be called vandalism) carried out in, or against, the name of art.

Civil War statue removals

Consider last year’s spate of Civil War-related sculpture removals in the United States. It began with the April demolition of the obelisk monument to New Orleans’ Battle of Liberty Place. Within weeks, a further three public sculptures — Confederate president, Jefferson Davis, and Confederate army generals Robert E. Lee and P.G.T. Beauregard — were removed from prominent New Orleans sites, often secretively and with sometimes bloody discord.

The city’s drive for a cleansing political correctness rapidly spread to other states in the former Confederacy. Social justice warriors, as they are now scathingly known, took special aim at public monuments and graveyard memorials. But streets, roads, hospitals, universities, and other public institutions also came under fire. Anyone lending a name or even a tenuous connection to the Confederate cause (and by default, slavery) became targets.

But what was the fire, at whom was it aimed, and whom ultimately did it burn?

Shooting the messengers

This dismantling of historical sculptures in the American south reflected a misguided attack on artistic values. In each case, the so-called social justice warriors shot the messengers, the monuments themselves.

The anti-monumentalists also destroyed a timely opportunity for historical balance and community cohesion. What better time has there ever been to review the nation’s turbulent Civil War through contemporary eyes? Why not engage in a consultative and consensual dialogue? What was wrong with re-writing the plaques and re-contextualising the fervour and the folly of both sides that produced some of America’s finest sculpture?

Speaking of monumentalists brings me back to my opening remarks. In other parts of this blog series, I refer to impressions of MONA, and the stance taken by its owner, some of its staff, and most of its many supporters.

‘I don’t understand art’

I recently explained to a client the technical detail behind a particular finish on a sculpture they’d commissioned me to make. In embarrassment, they could only splutter ‘I don’t really understand much about art.’

I had to pull myself up with a start when I realised my language took no account of their limited knowledge of either the processes behind sculpture or art in general.

Curse of knowledge

Without thinking, I’d fallen into the same trap of cultural superiority that I’d criticised MONA and some of its staff for. The syndrome has a name: the curse of knowledge. It describes situations where the strength and depth of your familiarity with a subject is so powerful, it blinds you to a lesser level of knowledge in others.

The syndrome is especially prevalent in academic, scientific, and other specialised circles of learning. Art is no exception. The greater the extent of specialisation, the worse the curse becomes. I apologised for my mistake, adjusted my language for clarity and inclusivity, and vowed never to fall prey to the curse again.

Coterie of smartarses

I’m grateful for the incident. It came as an apt reminder that, for the bulk of humanity, so much of art is at best smoke and mirrors. At worst, they see art as a cynical joke by a coterie of smartarses determined for unfathomable reasons to make ordinary people look and feel stupid.

I believe art is, and should be, an honest and true commentary that leaves its observers fuller, more resolved, and spiritually better connected with themselves and others. Art should allow viewers and participants an engagement at levels of their choice. If that includes giving participants the chance to stretch their imaginations, even better.

Artists who insist their work speaks for itself substitute hubris for humanity. If the work cannot make itself clear to a childlike curiosity, or to adult perception with the aid of an explanation in plain language, it replaces insight with insult.

Great art doesn’t dumb us down, it wises us up. It does so through simplicity, skill, ingenuity, and originality. It takes us by the hand and walks us side by side into a glowing landscape or vital edifice of the imagination, either as a dawn of awakening, or a dusk of acceptance.

Mediocre art substitutes a lack of talent with smotherings of obscurity and obfuscation, then blames us for not getting a point that was never there.

That, I maintain, is a MONAmental mistake.

Would you like to learn more about how to find, select, and buy beautiful sculpture? Call Todd Stuart on +61 4 5151 8865, or visit mainartery.art.

You might also like to visit or return to Parts 1 and 2 of this MONA blog series. Click on these links: MONA, sculpture, and the wank debate, or Just passing through — a visitor’s impression of art and sculpture.

For a general introduction to sculpture and the value it can bring to your life, go to Sculpture, our closest thrust to immortality.